I know how this essay will be read by many Christians, because I once read others the same way. With concern. With defensiveness. With a quiet sense that something precious is being threatened. The instinct is not malicious. It is protective. Faith, for many, is not merely a set of propositions, but a moral compass, a community, and a story that gives coherence to suffering.

So when someone leaves, especially without collapsing, it feels destabilising. Not simply because of disagreement, but because it calls into question what faith is assumed to be necessary for.

What follows is not an attack on Christianity, but an invitation to examine the assumptions that often sit just beneath the objections.

“You didn’t leave Christianity. You left a distorted version of it.”

This is usually meant kindly. It attempts to allow Christians to preserve the integrity of their faith while acknowledging my experience. It does so by suggesting that, somewhere, there exists a truer Christianity untouched by the concerns I raise.

But this response raises a serious theological problem.

Christianity has never existed in a single, unified form. It has always been plural, contested, and interpretive. From the earliest councils to the present day, Christians have disagreed on doctrine, ethics, authority, and practice. To claim that my critique targets only a “distorted” version is to assume access to a normative Christianity that stands above history, insulated from error, yet somehow identifiable.

Where, exactly, does this Christianity reside?

If Christianity is always mediated through human interpretation, culture, power structures, and historical context, then it cannot be meaningfully separated from the ways it is practised. To say “that’s not real Christianity” every time harm, exclusion, or incoherence appears is not a defence. It is an evasion.

“Without God, morality has no foundation.”

Christians often assume that without divine command, moral reasoning collapses into preference. But this assumption misunderstands both morality and divine command.

Even within Christianity, moral reasoning is unavoidable. Scripture does not interpret itself. Commands conflict. Contexts shift. Christians routinely weigh passages against one another. They routinely choose to prioritise between law and love, sacrifice and mercy, and conscience and literalism. These decisions are not dictated by revelation alone. They are made through human judgment.

The question is not whether we reason morally, but whether we admit that we do.

Appealing to God does not remove subjectivity. It relocates it behind claims of authority. The danger here is not disagreement, but unexamined certainty. When moral judgment is treated as divine fiat, it becomes insulated from critique, especially when it causes harm.

If morality requires infallibility to function, then Christian ethics has never functioned.

“You’re elevating human reason above God.”

This objection assumes a false alternative. I am not placing reason above God. I am acknowledging that reason is already there.

Every claim about God passes through human language, cognition, tradition, and interpretation. There is no unmediated access to divine will. Even the doctrine of revelation presupposes fallible human receivers. To deny this is not humility. It is theological naivety.

Ironically, refusing to acknowledge the role of reason does not honour God. It protects human interpretations from accountability.

If Christianity teaches anything about human fallibility, it should include our interpretations of God.

“Christianity has done immense good.”

Yes. And it has also done immense harm.

The honest Christian response to this reality should not be defensiveness, but discernment. The presence of good does not sanctify the whole. Nor does the presence of harm invalidate everything. The real question is whether Christianity contains reliable mechanisms for moral self-correction.

Historically, many of its moral advances have come not from doctrine itself, but from pressure outside it. Slavery was defended biblically before it was condemned morally. Patriarchy was sanctified long before it was questioned. Violence was justified long before it was spiritualised away.

Scripture did not change. Our moral imagination did.

Christians should be less concerned with defending Christianity’s past and more concerned with asking whether it can respond honestly to its present.

“This is emotional, not theological.”

This objection misunderstands both theology and humanity.

My departure was not born of resentment or crisis, but of sustained engagement with scripture, history, and ethics. Emotion followed reflection, not the other way around. And even if emotion were involved, that would not invalidate the conclusions.

Christianity itself is not emotionally neutral. It appeals to love, fear, guilt, hope, and longing. To dismiss doubt as emotional while sanctifying faith as virtuous is a double-standard Christians rarely notice in themselves.

If faith can be emotional and meaningful, doubt can be thoughtful and responsible.

“You’re throwing out the baby with the bathwater.”

I agree that not everything within Christianity is disposable. Ethical teachings, narratives of compassion, and models of self-giving remain valuable. But discernment is not the same as rejection.

Christian maturity should involve the ability to say, “This is good, and this is not.” To refuse that task in the name of loyalty is not faithfulness. It is fear.

What I have rejected is not wisdom, but the insistence that wisdom must be packaged as infallibility.

“You Were Never Really A Christian In The First place.”

One of the most common responses to my deconversion is not disagreement, but reclassification. If someone leaves Christianity and remains thoughtful, ethical, and whole, then the departure itself must be reinterpreted. This is where the No True Scotsman fallacy quietly enters the conversation.

The explanation is familiar. I must have been a backslider. Or never truly converted. Or insufficiently discipled. My faith must have been shallow, my commitment conditional, my experience incomplete. Something essential must have been missing, because if it were not, leaving would be impossible.

These claims are rarely offered with malice. They are offered with necessity.

They allow the belief system to remain intact by redefining the boundaries of belonging rather than confronting the possibility of error. Christianity is preserved not by answering the critique, but by excluding the critic. The category of “true Christian” is retroactively adjusted so that anyone who leaves no longer qualifies.

What this move cannot acknowledge is that sincere, committed Christians do leave. Not because they were pretending, deficient, or secretly rebellious, but because they took their faith seriously enough to follow the questions where they led. To deny this possibility is not theological confidence. It is epistemic self-protection.

“You Just Needed More Faith.”

Closely related is the suggestion that what enabled my deconversion was not the strength of the questions, but the absence of something else. More faith. A more powerful spiritual experience. The right sermon. The right apologetic argument. Some decisive encounter that would have resolved the tension and closed the gap.

This explanation is comforting, because it preserves the idea that Christianity works when properly applied. But it misunderstands the nature of the journey that led me away.

I did not leave Christianity because I lacked exposure to it. I left because I was immersed in it. My questions emerged from prayer, study, scripture, theology, history, and ethical reflection. They were not born of distance, but of proximity. I did not run out of experiences. I ran out of ways to honestly interpret them within the framework I had been given.

More faith is not a solution when the problem is that faith is being asked to carry explanatory and moral weight it cannot sustain. Nor is a powerful experience decisive in the way it is often imagined. Spiritual experiences are real and meaningful, but they are also profoundly shaped by expectation, culture, and interpretation. They tell us something important about human consciousness. They do not, on their own, adjudicate truth-claims about reality.

Some questions are not answered by intensity. They are clarified by honesty.

“You’re a Lost Sheep — You’ll Come Back”

Perhaps the most enduring narrative Christians reach for is the language of return. That I am searching. That I am restless. That in time I will realise what I was looking for was here all along. The story offers reassurance. Truth will reassert itself. The fold remains open.

I understand the comfort of this framing. It transforms departure into delay and preserves Christianity as the inevitable destination.

But it misrepresents my position.

I am not making dogmatic claims about whether God exists or does not exist. I am not closing myself off to mystery, transcendence, or meaning. What I am saying, with clarity, is that Christianity is not where God resides in the way it claims He does.

Christianity, as I have encountered it, does not reliably reveal God. It reveals power. It reveals hierarchy. It reveals the human impulse to sanctify certainty and protect identity. It tells us far more about ourselves than it does about the structure of reality.

If God exists, I see no reason to believe He is bound to a particular tradition, text, or institution. I see no reason to believe divine truth would require the suspension of intellectual honesty, the denial of evidence, or the outsourcing of moral responsibility.

If there is a movement toward God, it will not be a return to what I left. It will be a movement forward, not a regression reframed as homecoming.

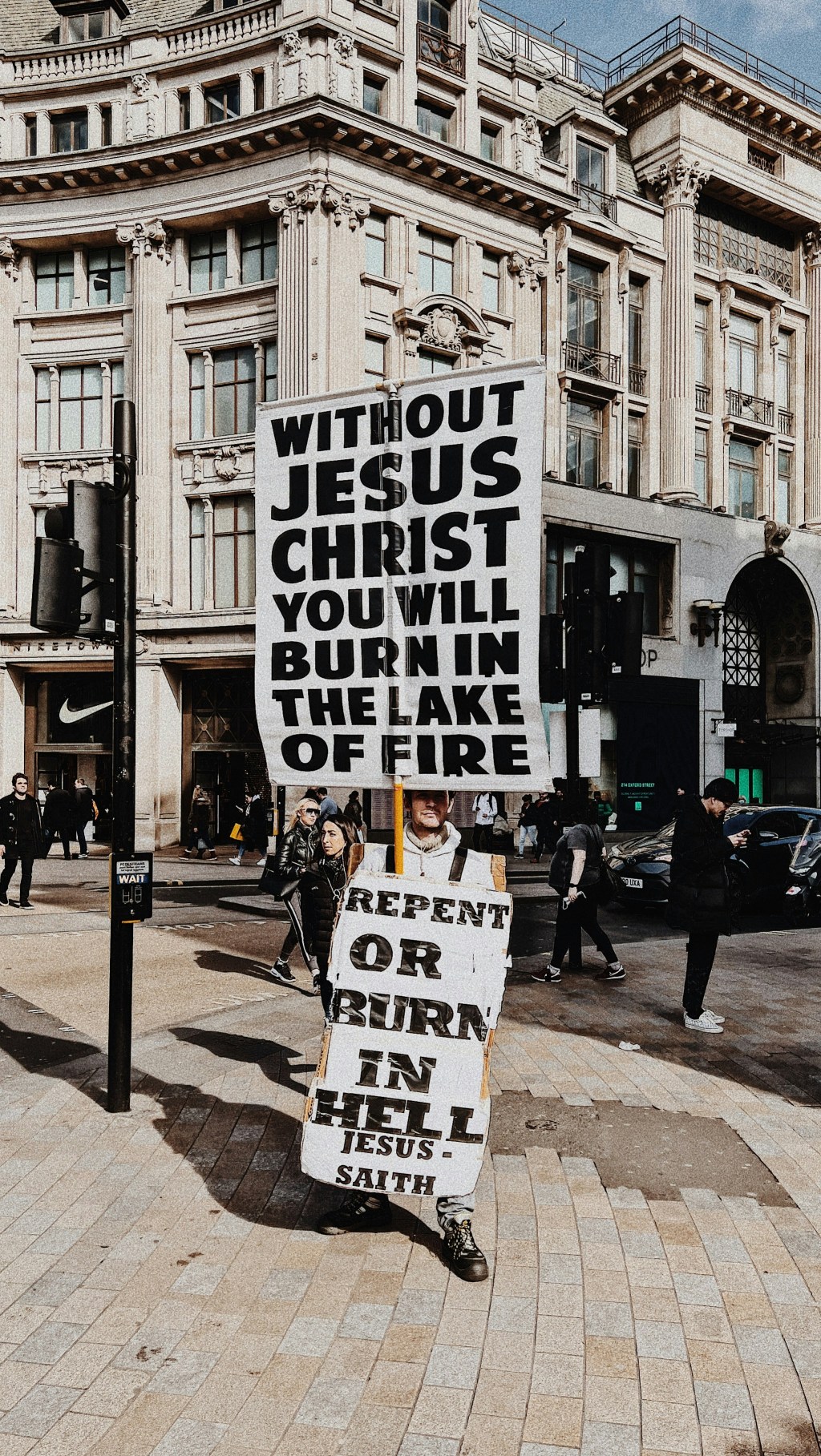

“IT Doesn’t Cost Anything to Believe. It Might Cost Eternity Not To.”

Eventually, many conversations arrive here. Beneath the intellectual objections and relational anxieties lies a deeper concern, often expressed with genuine care. What about your eternal destiny? What if you’re wrong? What if this costs you everything?

I do not doubt the sincerity behind this fear. For Christians who believe in eternal damnation, concern for my soul is not manipulative by definition. It is the logical extension of their theology. If hell is real and salvation exclusive, then to remain silent would be unloving.

But sincerity does not exempt an idea from scrutiny.

Appeals to eternal consequences often function less as arguments than as leverage. They shift the conversation from truth to risk management, from “Is this true?” to “Can you afford to be wrong?” This is the logic behind Pascal’s Wager, the suggestion that belief is the safer bet, because the potential loss is infinite.

The problem is that this wager assumes far more than it admits.

It assumes not only that God exists, but that Christianity’s account of God is correct. That this God rewards belief rather than honesty. That He punishes doubt rather than self-deception. That He prefers intellectual compliance over moral integrity. And that among the many competing religious claims about eternity, this particular version alone carries the correct stakes.

Pascal’s Wager does not lead to faith. It leads to anxiety.

More importantly, it reveals something troubling about the moral vision beneath it. A God who condemns people for sincere, reasoned disbelief while rewarding those who believe out of fear is not a God worthy of worship. Such a system does not elevate faith. It cheapens it. It turns belief into self-preservation and trust into calculation.

If God exists, and if He is just, then honesty cannot be a liability. Integrity cannot be a sin. And the pursuit of truth, even when it leads away from inherited certainty, cannot be grounds for eternal punishment.

I am not rejecting God to avoid responsibility. I am refusing to feign certainty where I do not have it. If there is judgment, I will stand on that choice without regret.

What I cannot accept is a theology that asks me to pretend belief in order to escape punishment. That is not faith. It is coercion, dressed in metaphysics.

And if the ultimate appeal Christianity can make is fear of what happens after death, rather than the goodness of what it produces now, that should give Christians pause. A truth that must threaten to be believed is already on unstable ground.

If there is a life after this one, I trust that whatever the beyond contains, it will judge me not by the flag I carried, but by the honesty with which I lived, the care I showed others, and the responsibility I took for the life I was given.

That is not a wager. It is a commitment.

A Final Word

What I hear beneath many of these objections is not certainty, but anxiety. Anxiety that truth is brittle. That morality cannot survive without surveillance. That growth must come at the cost of belonging.

I no longer believe that.

If Christianity is true, it should be able to withstand scrutiny. If it is good, it should be accountable to its consequences. And if it claims to reveal God, it should not be threatened by honesty about what it reveals instead.

I did not leave Christianity because I wanted less responsibility, less depth, or less meaning. I left because I could no longer reconcile the call to love truth with a system that too often protects certainty at its expense.

If that troubles you, I understand why.

But perhaps the deeper question is not why some of us leave, but why so many are taught to fear what happens when we do.

Leave a comment